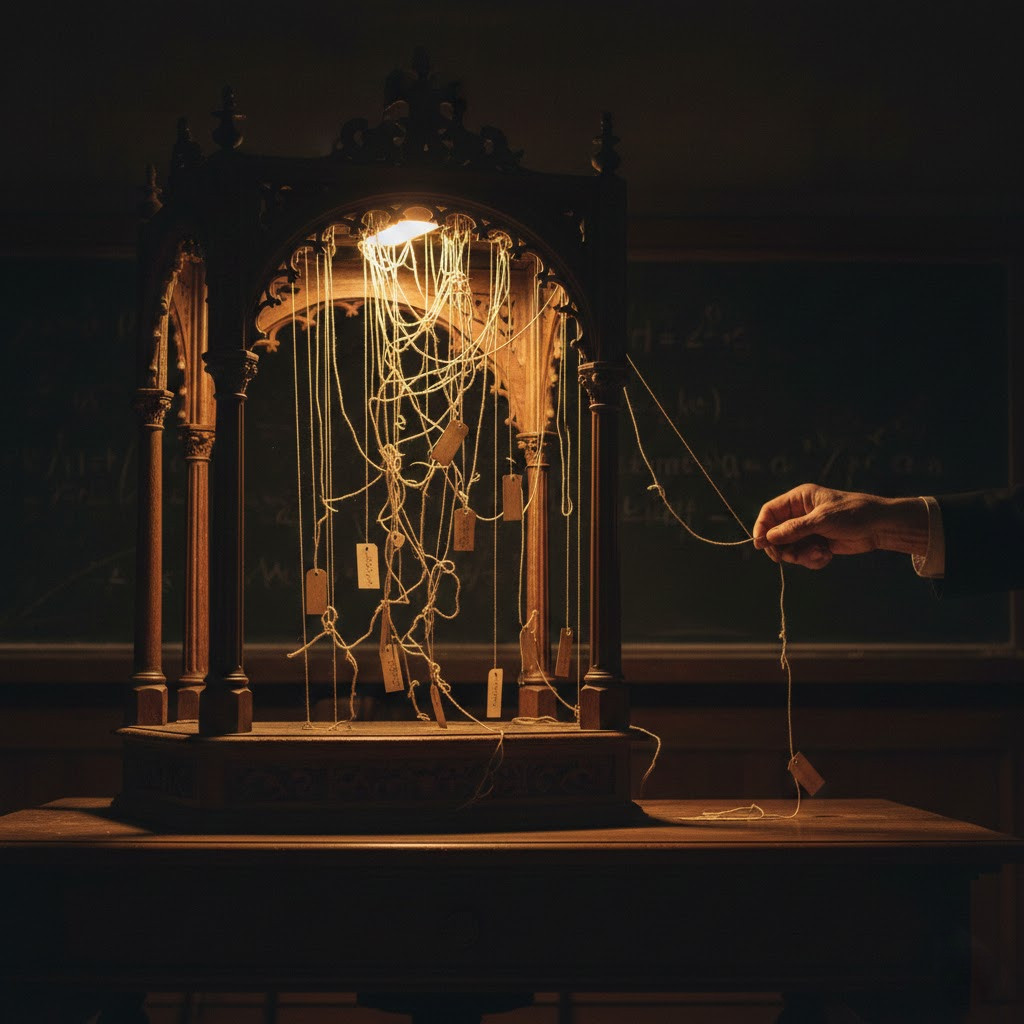

Why their arguments don't work, or how to pull on strings that are already dangling

The strings are dangling. You just have to pull.

The strings are dangling. You just have to pull.

"How do you write stuff like that without tripping over your own feet? The debates on evil, the Euthyphro dilemma, the First Cause, theistic evolution, the ambient anti-metaphysical mood... it makes my head spin. They're not right, but honestly, it's hard to refute them."

I get this question regularly, in various forms. Sometimes with a touch of admiration (flattering, but undeserved), sometimes with a hint of despair (understandable, and far more interesting). It usually comes from people who frequent places I would charitably describe as "intellectual septic tanks": r/philosophy, r/DebateAnAtheist, r/evolution, and sometimes even r/AskAChristian, where the Christian responses are often so limp they'd make St. Thomas weep.

I sympathize. I've spent entire evenings drowning in those threads myself, head in hands, wondering if I'd missed something. The problem of evil, formulated with surgical precision by someone citing Rowe and Draper. The Euthyphro dilemma, lobbed like an unpinned grenade into the middle of a thread. The First Cause "refuted" by a "well, who caused God then?" delivered with the quiet confidence of someone who thinks they invented the question. The systematic anti-metaphysical stance, which rejects all principled discussion in the name of an empiricism it never bothers to justify.

Yes, it makes your head spin.

And yet, the answer is almost insultingly simple.

The secret is that there is no secret

I'm not smarter than you. I'm not a better philosopher. I'm a computer scientist with a Ph.D. in artificial cognition, an irritating tendency to follow specious arguments far too long before realizing they're hollow, and an immoderate love for St. Thomas Aquinas that compensates, however poorly, for my gaps in formal training.

So how do I do it?

I check whether it's true.

Not "true" in the sense of "I like it," or "it confirms my biases," or "that's what the Church says." No. True in the most brutal, naked, indecent sense of the word: does this proposition correspond to reality? Does this claim say something about the world as it is, independently of what I think about it, what I feel about it, what I wish it were?

That's realism. And it's my entire arsenal.

Realism, that unbearable thing

Philosophical realism, in its Thomistic version, asserts something of staggering banality: there exists a reality external to our minds, and our intellect is capable of knowing it, imperfectly but truly. Things have natures. Causes produce effects. What is, is; what is not, is not. The principle of non-contradiction is not a linguistic convention; it's the very structure of reality.

Banal, isn't it? Almost boring. You'd think nobody contests this.

And yet, virtually every anti-theistic argument you encounter on Reddit rests, at some point or another, on a denial of these principles. Not always explicitly. Rarely consciously. But structurally, inevitably, fatally.

And that's where the strings start dangling.

Aikido, again and always

I've already written about argumentative aikido1: the technique of using the force of the opposing argument against itself. The more powerful the argument, the more devastating the reversal. Realism is the martial art that makes aikido possible: it's the mat on which everyone must stand, including the person who claims the mat doesn't exist.

Let's take the cases one by one. You'll see: once you've grasped the mechanism, it's always the same string dangling.

"Evil proves God doesn't exist"

The evidentialist argument from evil, in its strong version (Rowe, Draper, and their Reddit epigones), says essentially this: there exist sufferings so atrocious, so gratuitous, so manifestly pointless, that no good and omnipotent God could permit them. Therefore God doesn't exist.

First question, the only one that matters: what does "evil" mean here?

Because for the argument to work, evil must be really bad. Not "bad according to my subjective preferences." Not "bad according to my culture's conventions." Really, objectively, metaphysically bad. There must be a standard of goodness that is independent of our opinions, against which certain states of the world are genuinely deficient.

In other words: you need moral realism. You need good and evil to be realities, not projections. You need things to have purposes, natures, objective modes of flourishing.

And guess what all of that presupposes? A metaphysics. Essences. Natural ends. An order of reality that doesn't depend on us.

In short, precisely the intellectual framework that these same interlocutors rush to deny everywhere else, whenever it comes to rejecting the proofs for God's existence.

The string dangles: the argument from evil borrows half its premises from theism. It relies on a moral realism whose ultimate foundation, pushed to its logical conclusion, leads precisely to what it seeks to deny. It's an intellectual parasite eating the branch it's sitting on.

This doesn't mean that suffering doesn't raise real questions. It raises immense ones, and the Christian who claims to solve them with a snap of the fingers is either a liar or a fool. But the logical argument collapses the moment you pull the string: for evil to be a problem, good must be real. And if good is real, you're already in Thomistic territory, whether you like it or not.

"Euthyphro settled it 2,400 years ago"

Ah, Euthyphro. The favorite warhorse of r/DebateAnAtheist. "Does God command what is good because it's good, or is it good because God commands it?" If the former, then goodness is independent of God, and God is superfluous. If the latter, then morality is arbitrary, and God could command the murder of innocents.

Brilliant, isn't it? Airtight, even.

Except it's a false dilemma, and Thomas Aquinas solved it in the thirteenth century with a clarity I've never seen matched on Reddit2. The Thomistic answer is: neither. Goodness is not an external standard to which God submits, nor an arbitrary decree of His will. Goodness is God's very nature. God is Goodness, in the sense that He is the pure act of being, the plenitude of perfection from which all participated goodness derives.

But wait. To understand this answer, you must accept that things have natures. That goodness is not a label we slap on our preferences, but something real, rooted in the metaphysical structure of the world. You need realism.

And what do the people who brandish the Euthyphro dilemma do? They presuppose, by the very act of posing the question, that morality is something real enough and important enough to wonder about its origin. If they were consistent with their anti-realism, they wouldn't even ask the question: in a world without essences or natures, "good" is just a grunt of approval, and the dilemma vanishes for lack of combatants.

Another dangling string.

"Who created God?"

The objection to the First Cause. A classic. "If everything has a cause, then God has a cause too, so the argument is invalid, checkmate, thank you, good night."

I shouldn't even have to answer this, but since it gets served to me every three days, let's go.

The First Cause argument does not say "everything has a cause." It says: "everything that passes from potency to act requires an external cause already in act." Or, in its Leibnizian version: "every contingent being requires a sufficient reason for its existence." God, by definition, is not contingent and does not pass from potency to act. He is pure act. The question "who created God?" makes about as much sense as "who is the married bachelor?": it violates the very terms of what it claims to attack.

But notice the pattern: to even formulate the objection, you must accept that causality is real, that things have explanations, that the principle of sufficient reason has some force. Otherwise, why bother asking "who caused X"? If causality is merely a psychological habit à la Hume, if brute facts are possible, if nothing requires an explanation, then the objection itself loses all its bite.

Those who deny the First Cause must, in order to deny the First Cause, use the very principles that ground it. The string doesn't just dangle here: it's dragging on the floor.

"Metaphysics is hot air"

And here's the big one. Anti-metaphysics. The nerve center of the whole operation. "Metaphysics isn't knowledge. Only empirical science produces knowledge. Metaphysical questions are pseudo-questions."

This is logical positivism, risen from the dead by people who apparently didn't read the obituary3. But let's set aside the historical irony and go straight for the heart.

Is the claim "only empirical science produces knowledge" itself a claim of empirical science? No. It's a philosophical claim, more precisely a metaphysical one (it says something about the nature of knowledge and the limits of knowable reality). It's a thesis in epistemology, and epistemology is a branch of philosophy.

So anti-metaphysics is a metaphysical position.

This is the performative self-contradiction in all its splendor, aikido in its chemically pure state. The proposition destroys itself in the act of being stated. And this isn't a rhetorical sleight of hand: it's an inescapable logical consequence of the fact that every proposition about the nature of reality is, by definition, metaphysical. You cannot step outside of metaphysics. You can only do bad metaphysics while believing you're doing none.

Étienne Gilson had a magnificent phrase: "Philosophy always buries its undertakers."4 One might add: so does metaphysics.

The repeating pattern

You see the pattern now? It's always the same:

- An argument is presented against theism (or against metaphysics, or against moral realism).

- That argument, to have any force whatsoever, presupposes some form of realism (moral, causal, metaphysical).

- That presupposed realism is precisely what the interlocutor rejects everywhere else.

- You pull the string. The argument collapses, not because you've "refuted" it from the outside, but because it has refuted itself from the inside.

This is why I keep coming back to realism. It's not an ideological commitment. It's not a leap of faith. It is, in the strictest sense of the term, the condition of possibility of all rational discourse. Including atheist discourse. Including anti-metaphysical discourse. Including the discourse that claims to deny it.

Realism is true. And that's why it's so hard to get rid of: every attempt to deny it confirms it.

"So it's easy, then?"

No. No, it's not easy. And if you think I sit down at my screen with unshakeable confidence and a ready-made answer to every objection, you're sorely mistaken.

There are nights when a well-crafted argument makes me doubt. When the formal precision of an analytic philosophy paper gives me the impression that I've missed something crucial. When the sheer mass of objections, even mediocre ones, produces an accumulation effect that starts to resemble argumentative force.

It felt like that for years. Literally, years. And then, by dint of reading, of working through the arguments one by one, of turning them over and over, of honestly looking for the flaw I might have missed, I realized there wasn't one. Not out of bravado. Through methodical attrition. You end up knowing the arguments the way a mechanic knows an engine: not because you're brilliant, but because you've spent enough time under the hood.

And when the anguish comes back despite everything (because it does come back, don't worry), I use a technique I've come to call the reverse steelman. I tell myself: "All right. Suppose the opponent is entirely correct. Concede everything. Every premise, every inference, every conclusion." And I watch what happens. In the vast majority of cases, the position thus conceded destroys itself in three moves, because it ends up denying the very conditions of its own intelligibility. Anguish is fog; the steelman is a gust of wind.

And at bottom, there's something simpler still. God is truth. That's not a metaphor. That's not a catechism slogan. It's a metaphysical thesis of staggering radicality: the very being of God is truth, and every participated truth, including the truth of the argument that's worrying you, is merely a reflection of Him. If that's the case, then truth is always worth following, even when it hurts, even when it unsettles, even when it seems to threaten your faith. And if someone tells you there is no such thing as truth, ask yourself one question: then what are you doing looking for it?

And then I step back. I breathe. And I ask the question that undoes everything else: does the person telling me this believe what they're saying is true?

If they do, they're a realist, and the rest follows.

If they don't, I'm talking to someone who's announcing that their own words mean nothing. And at that point, as Aristotle said, you might as well argue with a houseplant.

The real problem

The real problem, in truth, isn't intellectual. The arguments are solid. Realism holds. Thomistic metaphysics has a coherence that two thousand years of criticism have failed to seriously dent, despite what the Reddit threads say between two memes about the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

The real problem is loneliness.

Defending philosophical realism in 2026 is a bit like defending Latin poetry at a growth-hacking conference. You're right, everyone vaguely senses it, but no one dares say so because the ambient consensus has decreed these questions "outdated." And the social pressure of intellectual mediocrity is a formidable force, far more formidable than a faulty syllogism.

That's why I write. Not because I have all the answers. Not because I'm sure of myself. But because someone has to say, calmly, patiently, with all the necessary irritation and not a gram more: the strings are dangling, you just have to pull them.

And if you're hesitating, start with the biggest one: ask your interlocutor whether what they're telling you is true. Not useful. Not socially acceptable. Not scientifically verifiable. True.

You'll be surprised how many positions collapse at that single word.

See my post "An effective antidote against specious arguments, or the art of argumentative aikido." The technique hasn't changed. It's just had time to mature.

To be perfectly honest, I'm not sure anything can be matched on Reddit, with the possible exception of the ability to produce strawmen at an industrial rate.

Logical positivism died when its own defenders realized that the "verification criterion" (every meaningful proposition must be empirically verifiable) is not itself empirically verifiable. Ayer more or less admitted it. But ghosts are hard to kill on the internet.

Gilson, Étienne, The Unity of Philosophical Experience, 1937. If you're going to read only one book on metaphysics in your life, read that one. Or the Summa, obviously. But Gilson has the advantage of being shorter and not requiring a Latin dictionary.