What even is a final cause, or why your morning hot chocolate refutes materialism

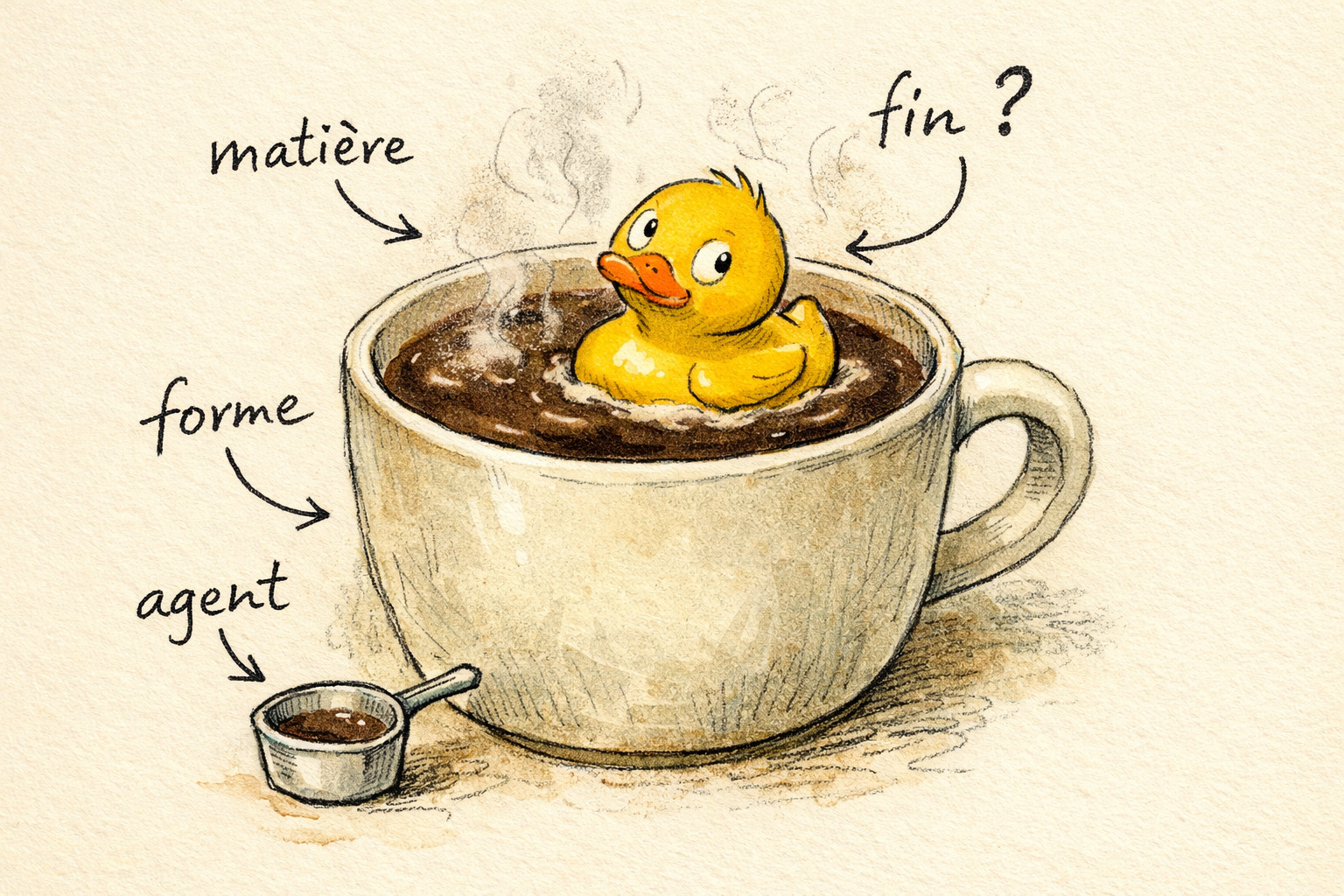

A rubber duck sitting in a cup of hot chocolate, surrounded by a sketch of Aristotle's four causes. Because if an acorn can become an oak, surely it can become a duck. Apparently not.

"But what's the point of a final cause?"

Again? Not that the question is stupid (it isn't), but the answers usually given to it are, quite spectacularly so. Confusion with intelligent design, "outdated Aristotle stuff debunked since Galileo," polite incomprehension from a computer scientist who should probably stay in his lane: there's work to do.

Let's start at the beginning, that is, with what the final cause is not. Because it's easier to clear the rubble before you build.

What the final cause is not

The final cause is not a "conscious purpose."

This is the most common misunderstanding, and probably the most destructive. When people hear "final cause," they immediately picture an intention, a plan, a little homunculus inside the thing deciding where it's going. We project our experience of human intention onto the concept, and promptly conclude that speaking of final causes amounts to saying that the falling stone wants to fall, that the heart decides to beat, that the tree wishes to grow toward the light. And since all of this is obviously absurd (and it is), we throw the concept out with the bathwater.

The problem is that we never understood the concept. We understood a caricature, which is not quite the same thing.

The final cause requires no consciousness, no deliberation, no mental project in the agent that acts. The ant has no business plan. The acorn hasn't read an arboriculture manual. And yet both are directed toward something determinate. It is this directionality, this regular orientation toward a specific result, that constitutes finality, not whatever awareness one might have of it. The vast majority of final causes in nature operate without the slightest thought. Welcome to reality.

The final cause is not "intelligent design."

I insist, because the confusion is stubborn. Intelligent design, whatever one thinks of it, is a theory about a designer external to the thing. The final cause, in the philosophical sense, is about the thing itself and what it is intrinsically ordered toward. It is a property of the agent and its action, not a label slapped on from the outside by a cosmic architect. Confusing the two is like confusing "fire heats" with "someone lit the fire." These are two perfectly distinct questions. One does not presuppose the other.

The final cause is not a temporally final cause.

The word "final" misleads everyone. You hear "final" and you think "at the end," "at the finish," "when it's all over." As if the final cause of an acorn were the oak tree that grows afterward. No. The final cause is that for the sake of which the agent acts, and it is operative from the very beginning, in the action itself. It is "final" in the sense of end, meaning goal, not in the chronological sense. The acorn's goal is not lounging at the end of the process smoking a cigarette: it structures the entire process, from within, from the very first cell. If you prefer: the final cause is first in the order of intention (it's what "launches" the process), though last in the order of execution (it's what gets realized at the end). This distinction is crucial, and if you miss it, everything else becomes unintelligible.

The final cause is not an efficient cause.

This one I'm going to hammer home, because it is the mother of all confusions, the one that spawns every other, and the one that makes conversations on the subject systematically sterile.

The efficient cause is what produces the change. It's the impact, the push, the chemical reaction, the engine, the hammer blow. It's the "what made it move?" The final cause is that toward which the change is directed. It's the "what for?", the "for the sake of what?" These are radically different questions, which call for radically different answers, and which are not interchangeable.

Why do I insist? Because modern philosophy has gotten into the habit of reducing all causality to efficient causality. When a modern hears "cause," he immediately thinks of a cosmic billiard table: one ball hits another, which hits a third, and so on. In this framework, there is room only for "what pushes what." And when you mention a final cause, he hears yet another efficient cause, but a mysterious, hidden, slightly magical one, a sort of invisible force that would pull things forward instead of pushing them from behind. As if the final cause were a phantom hand grabbing the acorn and dragging it toward its oak-tree form.

That is not what it is. At all. The final cause is not an agent. It pushes nothing, pulls nothing, exerts no force. It is not in the same register. The efficient cause answers "by what is the change produced?"; the final cause answers "toward what is the change ordered?" Confusing the two is like confusing a car's engine with its destination. The engine makes the car move (efficient cause). Lyon is where I'm driving (final cause). Lyon does not push my car. Lyon doesn't do anything at all. Lyon orients my journey. It's not the same thing, and as long as you haven't grasped this distinction, you're going in circles, without any apparent final cause, incidentally.

The final cause is not a scientific hypothesis.

It does not belong to the same register as "gravity is proportional to the inverse square of the distance." The final cause belongs to the philosophy of nature, that is, to the analysis of the principles of change, not to the mathematical description of its regularities. Modern science, since its founding, has chosen (with remarkable success, don't put words in my mouth) to limit itself to material and efficient causes, i.e. to "what is it made of" and "what pushes it." Very well. But limiting your method to two types of causes does not prove that the other two don't exist. If I decide to measure only the temperature in my kitchen, I haven't proved that atmospheric pressure is a myth. I've proved that my thermometer only measures temperature. Which will surprise no one.

What the final cause is

Good. The rubble is cleared. Let's build.

Aristotle distinguishes four causes1, that is, four ways of answering the question "why?" about a thing that changes. Let's take a deliberately simple example, so nobody gets lost: a cup of hot chocolate.

Why does this cup of hot chocolate exist? We can answer in four ways:

The material cause: what is it made of? Ceramic, hot milk, cocoa, etc. That's the matter, the substrate.

The formal cause: what makes it this and not something else? The form, the structure, the organization that makes a heap of ceramic and brown liquid a cup of hot chocolate and not a pile of wet debris. It's what makes the thing intelligible, what lets you recognize it.

The efficient cause: who or what produced it? The potter for the cup, myself (or my saucepan, let's be honest) for the chocolate. That's the agent of change, what makes the thing pass from potency to act2.

And finally, the final cause: for the sake of what? Why make a cup of this shape? Why heat milk with cocoa? To drink, to warm up, to survive a Monday morning. The final cause is the that for the sake of which a thing acts or is made. It's what the entire process is ordered toward.

Notice something important: the four causes are not in competition. They don't substitute for one another. You don't choose between the efficient cause and the final cause like you'd choose between two dishes at a restaurant. They are complementary, each illuminating a different aspect of the same phenomenon. Saying "the efficient cause of the hot chocolate is the saucepan" in no way eliminates the question "and for the sake of what does the saucepan do this?" These are two different floors of the same explanation.

"Sure, but that's for human artifacts. In nature, there's no final cause."

Ah. Here we go. The big objection.

Let's think about it seriously, if you don't mind, instead of swallowing it as self-evident. The objection amounts to this: fine, the craftsman makes the cup for the sake of drinking chocolate, that's trivial. But in nature, nobody made anybody for the sake of anything. The heart pumps blood, sure, but not "for the sake of" pumping it. It simply happens that cardiac muscular contractions produce, through physical laws, a blood flow. Period. No finality, just mechanics.

The problem is that this position is extraordinarily difficult to hold coherently. Look closely.

When you say "the heart pumps blood," you're already saying more than pure mechanics. You're identifying a function. You're saying that the heart is for pumping blood, that this is what it does, that this is why it's there. And this functional identification is absolutely everywhere in biology. The eye is for seeing. The kidney is for filtering. Hemoglobin is for transporting oxygen. Try doing biology without ever using a single word that implies a function, a direction, a "for": you'll find it is rigorously impossible. Your biology course would become an inventory of blind particle movements, without organization, without meaning, without intelligibility. No one would understand anything anymore, including the biologist.

Some will say: "Yes, but that's just a manner of speaking. We say the heart is for pumping blood out of convenience, but in reality there's nothing but a blind causal process, and finalistic language is a useful shortcut."

Fine. Let's concede this for the sake of argument. But the problem doesn't disappear: it moves. For why is this "shortcut" always useful? Why does it work so well? Why, in a universe supposedly devoid of all finality, do things behave exactly as if they were finalized? Why does the acorn always produce an oak and never a duck? Why does hydrochloric acid always react with zinc in the same way? Why does each efficient cause regularly produce the same type of effect?

This regularity, this constant directionality toward a determinate result, is precisely what we mean by final cause. Not a little conscious ghost pulling the strings, but the brute, observable, undeniable fact that natural agents are ordered toward specific effects. That each thing acts according to what it is, and produces determinate effects and not just anything. To deny this is not to do science: it is to deny that science is possible, since science itself rests on the regularity of natural causes3.

"Okay, but this is just a disguised argument for God's existence, right?"

No.

I can see the objection coming (it arrives every time, with the regularity, as it happens, of a well-ordered final cause): "All this is a Trojan horse. You let finality in, and boom, God shows up through the back door."

Well, no. Admitting that final causes exist in nature is not concluding to the existence of a supreme being. It's not even getting close. It is observing a fact of natural philosophy: agents act toward determinate ends. Period. A coherent atheist can perfectly well admit natural finality without losing an ounce of his atheism. Aristotle himself never drew from the final cause, as such, a proof for the existence of a creator in the sense we understand it.

If certain arguments lead from natural finality toward more... vertiginous conclusions, it is through the addition of other premises, other distinctions, other reasonings that are not contained in the simple recognition of the final cause. There are intermediate steps, and each one demands its own justification. You don't leap from the acorn becoming an oak to the First Cause in a single bound: you have to climb each step, and each step can be contested on its own merits. It is the mark of an honest argument to admit this.

I'm not selling anything here. I'm clearing up a concept that has been butchered for four centuries, and that people cheerfully confuse with ten things it isn't. Let the reader draw whatever conclusions he wants: that's his problem, not mine. My job stops at showing that the final cause is a philosophical fact, not an article of faith.

The bottom line

Let's sum up. The final cause is the intrinsic directionality of the agent toward its proper effect. It's the fact that fire heats (and doesn't cool), that the acorn becomes an oak (and not a pelican), that acid attacks metal (and doesn't serenade it). It's the that toward which that structures all efficient causality and without which the very notion of "law of nature" no longer makes any sense.

Without final causality, there is no reason for a cause to produce this effect rather than any other. And if there is no reason for a cause to produce this effect, then there is no regularity. And if there is no regularity, there is no science. You can find this boring, scholastic, dusty, outdated. But I challenge you to construct the slightest coherent causal explanation without presupposing, even implicitly, that things are directed toward determinate ends.

While waiting for someone to take up this challenge (I'm in no rush), I'll finish my hot chocolate.

It is, I note, still warm. By pure blind mechanics, obviously.

Notes

Aristotle, Physics, II, 3 and Metaphysics, Δ, 2. The four causes are one of the pillars of natural philosophy, and one of the Stagirite's most enduring contributions. Don't tell me it's "outdated": that's like saying a building's foundations are outdated because they're at the bottom.

For the uninitiated: the act/potency distinction is one of the most powerful tools in Aristotelian metaphysics. The acorn is an oak in potency; the oak is an oak in act. The passage from one to the other is change. I'll spare you the full lecture, but trust me, it's worth the detour.

You often hear that science "banished" final causes. In reality, science presupposes natural finality every time it formulates a law. Saying "water boils at 100°C at sea level" amounts to saying that water, as water, is ordered toward this behavior under these conditions. Remove this ordering: there is no longer a law, there is only chance. And with pure chance, good luck doing physics.