Why I am a Darwinist AND a Catholic, or how Darwin naturalized God without knowing it

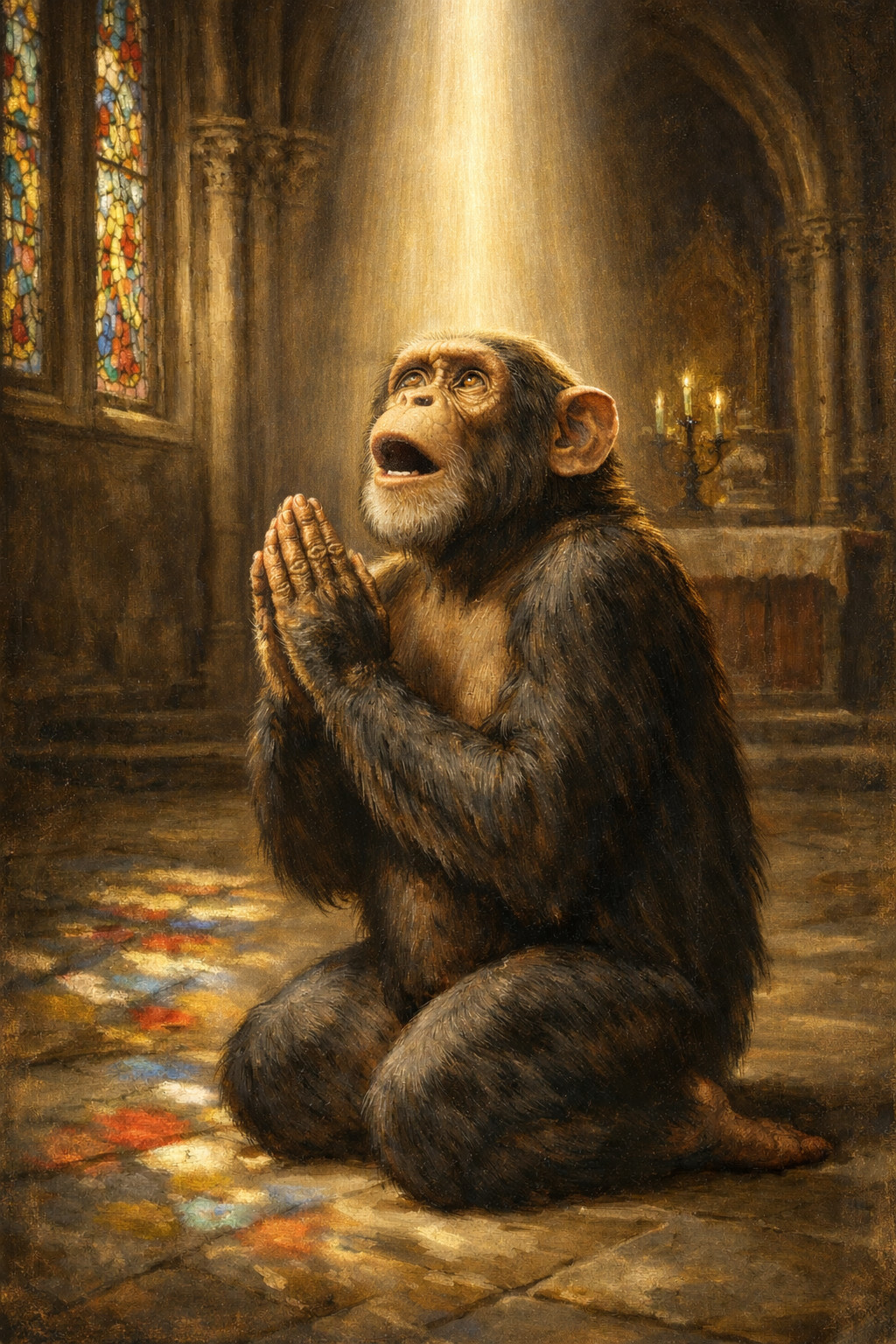

A praying chimp in a Gothic cathedral. Monod would call it absurd. Thomas would say the chimp is right. Darwin would note the chimp was selected for it.

A praying chimp in a Gothic cathedral. Monod would call it absurd. Thomas would say the chimp is right. Darwin would note the chimp was selected for it.

I recently listened to a debate featuring Kenneth Raymond Miller AGAINST creationism. For those who don't know him, Miller is a cell biologist at Brown University, a practicing Catholic, a recipient of the Laetare Medal from Notre Dame, and probably the man who most effectively demolished Intelligent Design in an American courtroom (Kitzmiller v. Dover, 2005). The kind of guy who quotes the Origin of Species in the morning and goes to Mass on Sunday. And who doesn't see the problem.

Neither do I.

And yet, I keep hearing the question, one time too many: "But how can you believe in God AND accept Darwin? Randomness, mutations, natural selection: that's the opposite of a divine plan, isn't it?" No. And I'm going to explain why, taking all the time it needs, because the subject deserves better than slogans. What follows is a defense, not of Darwinism against faith, nor of faith against Darwinism, but of intelligence against the intellectual laziness that thrives on both sides of the barricade.

Buckle up: we're going to talk metaphysics, molecular biology, and we're going to tackle Jacques Monod. Hard.

"Chance," the suitcase word nobody bothered to open

Let's begin at the beginning, and with the word that upsets everyone: chance.

I'm told: "Evolution relies on chance. Chance excludes design. Therefore evolution excludes God." It's clean, it's neat, it's a syllogism. And it's wrong, because the major premise is equivocal, meaning the word "chance" shifts its meaning between the first and second propositions, and nobody notices.

When the biologist says that mutations are "random," she is saying something very precise and very limited: mutations are not directed toward the future adaptation of the organism. That's it. She is not saying they spring from nothing, she is not saying they have no physico-chemical cause, she is not saying the Universe is a cosmic casino with no dealer. She is saying that the mutation on gene X doesn't "know" it will produce an adaptive advantage in environment Y. Darwinian chance is an absence of foresight at the molecular level, not an absence of causation.

Now, and this is where it gets interesting, in Thomistic metaphysics, chance (casus, or per accidens, in St. Thomas) designates the intersection of two independent causal series, each perfectly determined, whose conjunction was intended by neither of them taken separately. The classic example: I dig a hole in my garden to plant a tree and I find a treasure. My cause (digging) is determined. The cause of the treasure's presence (a stingy ancestor who buried it) is determined. Their intersection is "accidental" from the standpoint of each series taken alone, but this in no way means that a higher intelligence could not have willed, or permitted, this intersection within a larger plan1.

Thomistic chance is not a cause; it is a deficiency of particular finality at the crossroads of causes that are, themselves, perfectly finalized. And Darwinian chance is nothing other than this: the observation that the mutation, taken in itself, is not oriented toward the adaptive result that may follow later, after the filter of selection. To claim that this excludes all higher finality is to commit a logical leap quite spectacular in scale, the sort that would make your metaphysics professor blush, if you still have one2.

To be clear: the biologist's chance is epistemic (relative to our knowledge of future orientation) and methodological (relative to the operational framework of science). It is not ontological in the sense of excluding all ordination toward an end. To confuse the two is to transform a limitation of method into a claim about reality. It's as if a plumber, noticing that he can't fix a leak with a stethoscope, concluded that the heart doesn't exist.

Monod, or How to Go from Nobel to Metaphysics Without Changing Your Lab Coat

And this is where we need to talk about Jacques Monod, because he is the one who enshrined this confusion and elevated it to the rank of cultural dogma. Monod is, in a sense, the godfather of this error: he gave it institutional legitimacy, a Nobel Prize slung over his shoulder, and prose beautiful enough to make you forget to check whether it says something true3.

Monod, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965, brilliant biochemist, close friend of Camus, and author of Chance and Necessity (1970), a book I read with a mixture of fascination and mounting exasperation, rather like watching a brilliant surgeon attempt plumbing with his scalpel. In molecular biology, Monod is a titan. In philosophy, he's a tourist who forgot his map and who, because he has a nice backpack, thinks he's a mountaineer.

Monod's central thesis, summarized without doing him injustice: the "postulate of objectivity" of science, that is, the methodological refusal to invoke final causes in the explanation of natural phenomena, is not merely a method. It is, he says, the only rational attitude toward reality. And he concludes, in his famous peroration: "The ancient alliance is broken; man knows at last that he is alone in the indifferent immensity of the Universe from which he emerged by chance."

Magnificent. Tragic. Wrong.

Wrong, because Monod commits exactly the error I just described: he transforms a methodological prescription into an ontological conclusion. The postulate of objectivity says: "within the framework of my scientific research, I do not appeal to final causes to build my models." Very well. Nobody objects to this, and certainly not St. Thomas, who distinguished with crystalline clarity the different orders of causality and their respective domains. But Monod, in a slide that no longer belongs to science but to ideology, concludes: "therefore there are no final causes." It's as if a painter, because he only uses red and blue, concluded that yellow does not exist. The fact that your instrument does not detect something does not mean that something isn't there, especially when you deliberately built your instrument not to detect it4.

Let us be more precise, because Monod deserves it. There is, in Chance and Necessity, a logical error that recurs with the regularity of a metronome, and which I shall call, for lack of a better term, the microscope fallacy: "what my microscope doesn't show doesn't exist." Monod decides, in chapter one, that science will not concern itself with finality. Very well: this is a legitimate methodological choice, like deciding you'll only play with the white pieces in chess. But then, after playing the entire game with the whites, he looks at the board and triumphantly announces: "See! There are no black pieces!" Pardon me, Jacques, but you're the one who removed them. The postulate of objectivity excludes by construction finality from the field of investigation; to conclude that finality does not exist is to confuse the rules of the game with reality. It's a circular argument of considerable elegance, I'll grant him that, but a circular argument nonetheless.

And the problem doesn't stop there. Because Monod, as a good materialist, doesn't merely say that science has no need of finality (which is true and trivial). He says that finality is an illusion, an animistic residue, an anthropomorphic superstition that modern man must discard. That is, he transforms a methodological abstraction, the decision not to invoke final causes in models, into an ontological negation, there are no final causes in reality. This leap is so enormous you could see it from space, and yet it passes without comment because Monod writes well and nobody has read Aristotle.

But wait, because the best is yet to come. For Monod, while chasing finality out through the door, is about to let it back in through the window, wearing a disguise and a false nose. And that false nose has a name: teleonomy.

Teleonomy, or Finality That Dares Not Speak Its Name

Monod knew perfectly well that biology is saturated with finality. You cannot describe a living organism without speaking of function, of purpose, of project (his own term). The heart serves to pump blood. The eye is made to see. The kidneys have the function of filtering metabolic waste. All of functional biology is one immense finalistic discourse, from the first anatomy lecture to the latest article in Nature.

Problem: if the postulate of objectivity forbids final causes, how do you talk about "function" without betraying science? Monod's answer: you invent a new word. Instead of teleology (from the Greek telos, end, and logos, reason, literally: "reason of the end"), you say teleonomy (from the Greek telos and nomos, law). Teleology is ugly, metaphysical, scholastic, ugh. Teleonomy is clean, scientific, smells like a laboratory.

And the difference between the two? I'm waiting.

No, seriously, I'm waiting. Because if you scratch the surface even slightly, you discover that Monod's "teleonomy" is exactly the intrinsic finality of Aristotle and St. Thomas, the directedness immanent to biological processes, but relabeled so as not to have to utter the offending word5. It is a remarkable case of what the English call a distinction without a difference. The label changed, but not the contents. They replaced logos with nomos, "reason" with "law," and declared themselves free from metaphysics. Bravo. It's a bit like renaming my dog from "Rex" to "Self-Directed Quadrupedal Domestic Loyalty Entity" and claiming to have solved the problem of canine nature. (I don't have a cat. I have a dog. Long live dogs. Dogs, at least, don't pretend to be autonomous; they embrace their finality, which is to love you unconditionally and steal your spot on the couch.)

Darwin Naturalized Finality (and Nobody Noticed)

And here is the central point of this article, the one that deserves a moment's pause, because it is both obvious and remarkably ignored.

It is often said that Darwin "eliminated finality" from biology, that he replaced "intelligent design" with the blind mechanism of natural selection, and that this is what made his revolution decisive. This is the standard narrative, the one taught in schools, the one Monod reprises, the one Dawkins hammers home with the enthusiasm of an atheist missionary. And it is, to put it politely, an extremely partial reading of what Darwin actually did.

What Darwin actually did is something far more subtle and, from a philosophical standpoint, far more interesting: he naturalized finality. He did not eliminate the language of ends; he translated it into the language of efficient causes. And this translation, far from suppressing finality, built it into the furniture of contemporary biological science.

Consider. All of modern biology is structured around a concept inherited from Darwin: function. The heart has the function of pumping blood. Hemoglobin has the function of transporting oxygen. The immune system has the function of defending the organism against pathogens. Try to write a biology paper, a single one, a single paragraph, a single abstract, without using the word "function" or one of its equivalents ("role," "purpose," "serves to," "is responsible for," "adapted for"). You can't. It's impossible. Biology is, de facto, the most finalistic science in existence. And it was Darwin who made it so.

Before Darwin, finality in biology was theological: the heart pumps blood because God designed it for that purpose (this is Paley's argument, from natural theology). After Darwin, finality is naturalized: the heart pumps blood because organisms whose hearts pumped blood survived and reproduced better than the others. The final cause (pumping blood) is reformulated in terms of efficient causes (natural selection acting on hereditary variation). But, and this is the crucial point, the logical structure of the explanation remains identical. It is still a "what for" that explains the "why." We have simply shifted the agent: instead of a conscious Watchmaker, it is the blind mechanism (but regular, but ordered, but oriented toward adaptation) of selection.

As Asa Gray, Harvard botanist, correspondent and friend of Darwin, and a convinced Christian, noted with delicious irony in an article in Nature in 1874: "The great service of Darwin to natural science has been to bring back teleology: so that instead of Morphology versus Teleology, we now have Morphology wedded to Teleology6." Read that again: Darwin brought back teleology, according to one of his closest collaborators. He didn't kill it. He made it respectable for naturalists.

And Darwin himself knew it. James Lennox, philosopher of science at Pittsburgh, has shown convincingly that Darwin deliberately used the language of final causes in his notebooks and in his publications7. Darwin did not consider that his theory eliminated teleology; he considered that it refounded teleology on natural grounds, without recourse to natural theology. A capital distinction: he did not deny finality; he denied that finality needed a designer immediate and conscious at every step.

The Heart Is Made FOR Pumping Blood (and You Can't Get Around It)

And this is where the affair becomes frankly comical. Because biologists, after noisily banishing teleology, spend their entire lives trying not to speak teleologically, and fail.

It is a classic pedagogical exercise in English-speaking evolutionary biology courses: students are asked to reformulate "teleological" sentences as "mechanistic" ones. For example:

"Teleological" version (forbidden): The heart is made for pumping blood.

"Mechanistic" version (approved): Organisms possessing an organ whose rhythmic contractions propelled blood through the vascular system enjoyed a selective advantage over organisms lacking such an organ, which led, through natural selection acting on hereditary variation, to the fixation of this structure in the population.

Magnificent. Fifty words instead of nine. But read the "mechanistic" version carefully. What does it actually say? That the heart is there because it pumps blood. That it is the fact of pumping blood that explains the presence of the heart. That the result (cardiac function) is the reason why the cause (cardiac structure) exists. This is exactly an explanation by final cause, dressed up in causal history, wrapped in a selectionist narrative, certainly, but structurally identical. The word "for" has simply been replaced by "was selected because," which amounts to exactly the same thing on the logical level: the effect accounts for the cause8.

As the biologist S.H.P. Madrell sums it up with thoroughly British pragmatism: the mechanistic reformulation is merely a rhetorical shortcut; it should not "be taken as implying that evolution proceeds other than by random mutations, those conferring advantage being retained by natural selection." Certainly. But if your non-teleological sentence says exactly the same thing as your teleological sentence, minus only length and tedium, then perhaps the problem isn't in the sentence but in your phobia of the word "for."

The Organ Creates the Function, the Function Creates the Organ: Metaphysically, Who Cares

And here we arrive at the great debate, the one that has occupied philosophers of biology for a good century: does the organ create the function, or does the function create the organ?

The "mechanist" camp says: the organ first. First, by chance (a mutation, an anatomical variation), a structure appears. Then, this structure happens to have a useful effect. And it is this useful effect that is retained by selection. Function is a by-product, an a posteriori result: the organ creates the function.

The "functionalist" camp says: the function first. The selective pressure (the need to pump blood, to see, to flee predators) is the reason why the organ exists. Without this pressure, the organ would not have been selected, and therefore would not exist in its current form. The function creates the organ, in the sense that it explains the organ's presence.

This debate is fascinating for biologists and philosophers of biology, and I won't settle it here (I'm only a poor Thomist computer scientist, after all). But from a metaphysical standpoint, I'll take the liberty of pointing out that both positions amount to exactly the same thing.

Why? Because in both cases, you have an ordination of structure toward a result. Whether you say "the heart was selected because it pumped blood" or "the fact of pumping blood explains why we have a heart," you're saying the same thing: there is a relation of ordination between a structure and an effect, and it is this relation that makes the structure intelligible. And this relation of ordination, in metaphysics, has a name, a very old name, a name that two millennia of philosophy have polished smooth like a pebble: final cause.

Whether the final cause operates through natural selection, or despite it, or by means of it, is a question of mechanism, not of metaphysics. The final cause does not say how the end is achieved; it says that the end is that for the sake of which the thing exists. And this, no mechanistic reformulation can eliminate, because this is precisely what the mechanistic reformulation explains, in detail, certainly, and with mechanisms, very well, but by explaining why the organ is there, which is the finalistic question par excellence.

St. Thomas, in his Commentary on Aristotle's Physics, notes that the final cause is "the cause of causes" (causa causarum), because it is what sets the efficient cause in motion. The mason lays the bricks (efficient cause) in order to build the house (final cause). The bricks don't "know" they're becoming a house; the mason does. And if someone tells me that in evolution there is no conscious mason, very well, I agree entirely: natural selection is not a conscious agent. But the absence of consciousness at the level of the mechanism does not entail the absence of finality at the level of being9. The river has no consciousness of flowing toward the sea, and yet it flows there. The absence of consciousness in the process is not proof of the absence of meaning in the result.

Monod on the Ropes (and He's Not Getting Back Up)

Let us return to our dear Monod, because I'm not finished with him. Not by a long shot. What came before was just the warm-up.

Monod acknowledges himself, and to his credit it must be said, that biology is saturated with what he calls "teleonomy," that is, the goal-directed character of biological processes. He writes, and I quote because it's too good: "Objectivity nonetheless obliges us to recognize the teleonomic character of living beings, to admit that in their structures and performances, they realize and pursue a project10."

You read that correctly. Project. That's Monod's word, not mine. The man who tells you that chance and necessity suffice to explain everything, that finality is an animistic illusion, that the Universe is indifferent and man is alone, this man writes, in black and white, that living beings "pursue a project." And he calls this a "profound epistemological contradiction," which is an elegant way of saying: "I've painted myself into a corner and I know it, but I'm hoping the beauty of my prose will make you forget the size of the problem."

How does he get out of it? By asserting that this apparent finality (teleonomy) is the result of blind processes (the chance of mutations and the necessity of selection), and that it therefore requires no external finalistic principle. Very well. But nobody was asking him for an external finalistic principle in the sense of a watchmaker tinkering with each organ; that's Paley, and Paley has been dead for a long time, and good riddance. What we're telling him is that the very structure of his explanation, processes that regularly, systematically, universally produce beings endowed with "projects," is itself finalistic. That the Universe is such that it produces finality is a fact considerably stranger than the one he claims to explain.

And this is where the shoe really pinches, where the house of cards collapses, where Monod goes from interesting error to involuntary farce. For look at what he does, in three movements:

First movement: he posits the postulate of objectivity, which forbids recourse to final causes. Very well. This is a methodological convention.

Second movement: he observes that biology cannot do without finalistic language, and invents "teleonomy" to save the furniture, that is, to keep talking about ends without admitting he's talking about ends.

Third movement: he concludes that man is alone in an indifferent Universe, because science shows no finality, even though he has just spent two hundred pages showing that science cannot do without it.

Read that again. This is a man who tells you, in the same book: (a) finality is an illusion, (b) biology cannot function without finality, and (c) therefore man is alone in the Universe. The conclusion follows from neither (a) nor (b), and (a) contradicts (b). This is, structurally, the most beautiful case of performative self-contradiction since the Eleatics, except that the Eleatics had the excuse of living in the fifth century before Christ and of not having read Aristotle. Monod has no such excuse. Monod read Aristotle. He read him, and decided to disregard him, which is worse.

Because the real problem with Monod, the foundational problem, the one that makes Chance and Necessity not wrong in detail but wrong in architecture, is that he systematically confuses two radically different questions:

The first question: "How did living organisms become what they are?" This is a scientific question, and the Darwinian answer, mutation, selection, drift, time, is excellent. Nobody contests it here. This is the question of mechanism.

The second question: "Why is there a Universe in which blind processes regularly, inevitably, produce beings capable of asking questions about the Universe?" This is a metaphysical question, and the Darwinian answer doesn't address it, not because it's insufficient, but because this isn't its kind of question. This is the question of being.

Monod takes the first question, answers it brilliantly, and acts as if he had answered the second. This is the central sleight of hand of the book, and it is the point on which one must be merciless: when Monod writes that man is alone in the indifferent immensity of the Universe, he does not deduce this conclusion from his biological data. He pastes it on top. It is an existential choice, respectable as a choice, but fraudulently presented as a scientific conclusion. Monod's molecular biology is impeccable. His philosophy is an exercise in smuggling: passing off an existential anxiety as a laboratory result.

And the final irony, the one that should make every Thomist within a thirty-mile radius weep with laughter: Monod, by showing that the Universe necessarily produces complexity, consciousness, and "teleonomy" through regular natural laws, did not demonstrate the absence of God. He demonstrated exactly what St. Thomas's Fifth Way has affirmed since 1265: that beings devoid of knowledge act toward an end with a regularity that can only be explained by an ordering intelligence. Monod re-derived the Fifth Way while believing he was refuting it. He naturalized the argument, dressed it in biochemistry, and presented it as proof of the absurd, when it is, structurally, proof of the opposite. Chance and Necessity is, unbeknownst to its author, one of the most beautiful arguments for the existence of God written in the twentieth century11.

The True Catholic Position (and Why It's More Demanding Than You Think)

Right. Enough hitting. Time to build.

So what is the Catholic Church's position on evolution? It is both simpler and more demanding than either its detractors or its ill-informed defenders imagine.

What the Church does not teach: that Genesis is a biology textbook to be taken at face value. That the Universe is six thousand years old. That species were created separately and simultaneously. That Darwin is a heretic. That the theory of evolution is incompatible with faith. All of these positions belong to American Protestant fundamentalism, not to Catholic theology, and anyone who attributes them to the Church knows neither the encyclical Humani Generis of Pius XII (1950), nor John Paul II's address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences (1996), nor the four senses of Scripture that the Church has taught since... well, since always12.

What the Church teaches: four things, essentially.

First, that scientific investigation into the mechanisms of evolution is legitimate, free, and even welcome. As Pius XII recalled in Humani Generis: research into the origin of the human body from pre-existing living matter is open to the investigation of theologians and scientists alike. Science does its work; theology does its own. There is no conflict, unless you've misunderstood one or the other.

Second, that the human soul is immediately created by God. This is not an optional add-on; it is non-negotiable. The Church radically distinguishes the biological order (the body, its mechanisms, its evolutionary history) and the spiritual order (the rational soul, consciousness, freedom, openness to transcendence). Evolution can perfectly well account for the emergence of the human body from earlier primates; it cannot account for what makes man a spiritual being. Not because science is "limited" (though it is, like any discipline), but because the soul is not of the same order of reality as the body. It's like asking an acoustician to explain the beauty of the Mass in B Minor: he can explain the frequencies, the harmonics, the resonances, and he will not have said a single word about what makes Bach Bach.

Third, that creation is not a past event but a permanent act. The God of St. Thomas is not a watchmaker who wound up the mechanism and watches from afar. He is Pure Act, Ipsum Esse Subsistens, Being itself, who maintains each thing in existence at every instant. To create, for God, is not to manufacture a watch and let it run; it is to be the reason why there is something rather than nothing, now, at this second. And in this perspective, evolution is not a process alongside creation, in competition with it: it is a mode through which creation unfolds in time. Natural selection, mutation, genetic drift, all of these operate at the level of secondary causes. And secondary causes presuppose a First Cause, as waves presuppose the ocean.

Fourth, and this is where things become truly demanding: the Catholic position refuses both creationist fideism (which denies science in the name of faith) and materialist scientism (which denies metaphysics in the name of science). It demands holding both ends: yes, evolution is the best available scientific model for accounting for the diversity of life; and yes, the existence of life, of consciousness, of the intelligibility of reality, points to questions that science cannot resolve because they do not belong to its domain. The Catholic has no intellectual right to choose comfort: neither the comfort of blind faith that refuses to look at the fossils, nor the comfort of lazy materialism that refuses to look at the question of being.

Is this uncomfortable? Yes. This is the adult's position. The creationist and the scientistist have this in common: they both want a simple answer. One says: "God did everything, move along." The other says: "Chance did everything, move along." The Catholic says: "It's more complicated than that, sit down, this is going to take a while." And I understand that's not a great sales pitch13.

The Final Word

Darwin didn't kill God. Darwin killed a certain image of God, that of Paley's Watchmaker, the divine tinkerer who adjusts each butterfly wing and each bacterial flagellum with tweezers. And good riddance, because Paley's argument was already a philosophical catastrophe before Darwin demolished it scientifically.

Why? Because Paley's "God" is not God. He's a craftsman. A super-engineer. A very competent technician who makes stuff. The analogy of the watch found on the heath, "if you find a watch, you infer a watchmaker," poses an immediate metaphysical problem that Paley doesn't even see: it reduces God to an efficient cause among others. The watchmaker is within the world; he works with pre-existing matter, according to laws he did not create, in a time he did not institute. He is, at best, a demiurge, the God of Plato's Timaeus, the one who arranges matter, not the one who creates it. But the God of Christian theology, the God of St. Thomas, is not an arranger. He is Being itself, Ipsum Esse Subsistens, the One who gives existence as such. He doesn't tinker with a watch: he is the reason there is metal, time, physical laws, and watchmakers. The distance between the two is infinite, literally.

Worse still: Paley's argument is a theological time bomb, because it implies that the more science explains, the less room there is for God. If God is the explanation for the "gaps," what the anglophone world calls the God of the gaps, then every scientific advance pushes him a little farther away. This is exactly what happened: Darwin provided a natural mechanism for biological complexity, and everyone concluded that God had become superfluous. But God was only "superfluous" because Paley had put him in the wrong place, wedged into the interstices of scientific explanation instead of situating him where he actually is: at the foundation of existence itself.

Paley's God is a god you can do without once you've found the mechanism. St. Thomas's God is the One without whom there would be no mechanisms at all. Darwin refuted the first. He didn't touch the second, he couldn't touch the second, because the question "why is there something rather than nothing?" is not within the purview of biology, or of any empirical science. Paley thus did Christian theology a very bad turn: by selling an easy god, he prepared the ground for an easy refutation. The loudest atheists of the twenty-first century, Dawkins chief among them, refute Paley with brilliance and believe they have refuted theism. It's as if someone burned a portrait of you and claimed to have murdered you.

The God of the Catholic faith is not an agent among agents, another cog in the cosmic machinery, an extra "hypothesis" to fill in the gaps of science. He is that without which there would be neither machinery, nor science, nor gaps to fill. He is the reason there is something rather than nothing, and, incidentally, the reason this something is intelligible, that is, accessible to a human reason which itself had no obligation to exist.

Monod ended his book with a lament, a tragic cry into the void: man alone, lost, abandoned in the indifferent immensity. It's beautiful. It's even very beautiful, Monod wrote admirably, that much must be granted. But it's a choice, not a demonstration. It's Camus in a lab coat, existentialism passing itself off as biochemistry. And it is, as I have shown, contradictory with the very content of the book that precedes it. Monod spent two hundred pages proving that the Universe regularly, through stable and intelligible laws, produces beings endowed with "projects," and he concludes that all of this means nothing. That's his right. But let him not call it science. It's a mood.

Faced with the same facts, a Universe that produces complexity, consciousness, beauty, finality through regular and intelligible laws, the Christian makes another choice, one no less rational and infinitely more joyful: to recognize, in the prodigious order of living things, not the silence of the absurd, but the voice of the One who said, once and for all, and who continues to say at every instant: let there be light.

And there was light.

Notes

Cf. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles, III, 74: "What seems to occur by chance with respect to the lower cause is ordered with respect to the higher cause."

For those who lack one, I recommend a good Thomist. You can still find them, if you look hard enough. They're a bit dusty but they work.

I could have gone after Dawkins, but Dawkins tackles himself with such efficiency that it would be redundant. And besides, his militant atheism has something so naively Victorian about it that I'm almost fond of him.

Étienne Gilson demonstrated this confusion marvelously in From Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again (1971), a book I recommend to anyone who wants to understand the relationship between biology and finality. It's short, it's lucid, it's devastating.

The supreme irony is that nomos (law) is, if anything, even more finalistic than logos (reason). A law implies a legislator, a regularity ordered toward a result. In trying to flee finality, Monod chose a word that implies it even more. Thank you, Jacques.

Gray, Asa, "Darwin and Teleology," Nature, 1874. Gray is a fascinating figure: the first American Darwinian, a first-rate botanist, and a convinced Presbyterian. Darwin esteemed him deeply while being disturbed by his theistic reading of natural selection. Proof that the debate is not new.

Lennox, James G., "Darwin was a Teleologist," Biology and Philosophy, 8, 1993, pp. 409-421. Magnificent title and solidly argued thesis.

Philosophers of biology call this an etiological explanation of function: the function of a trait is the effect for which it was selected. See Wright (1973), Millikan (1984), Neander (1991). All of them recognize that the logical structure is that of an explanation by final cause. They're simply too polite to call it teleology in front of their colleagues.

St. Thomas distinguishes the finis operantis (the end of the agent, which requires consciousness) and the finis operis (the end of the work, which is inscribed in the nature of the thing). The arrow flies toward the target without knowing it. It flies toward the target no less for that.

Monod, Jacques, Chance and Necessity, Knopf, 1971 (original French: Le Hasard et la Nécessité, Seuil, 1970), chapter I.

I am not joking. Reread the Fifth Way (Summa Theologiae, Ia, q. 2, a. 3): "Things which have no knowledge do not act toward an end unless they are directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence, as the arrow is directed by the archer." Now reread Monod: blind processes (mutations) regularly produce beings oriented toward ends (teleonomy). The structure is identical. Monod simply replaced "arrow" with "DNA" and "archer" with "natural selection." The Thomistic question remains intact: who made the bow? Monod doesn't ask the question. He doesn't ask it because his postulate of objectivity forbids him from asking it. And he confuses this methodological prohibition with an answer. It's like putting your hands over your ears and concluding that silence reigns.

Literal, allegorical, moral, anagogical. Four senses, not one. When an atheist quotes Genesis to me literally in order to tell me I should believe it literally, I always wonder which of us is the fundamentalist.

If you're looking for a faith that doesn't require intellectual effort, I recommend the New Age. There are crystals, chakras, and nobody will ask you to read the Summa Theologiae. It's more restful.