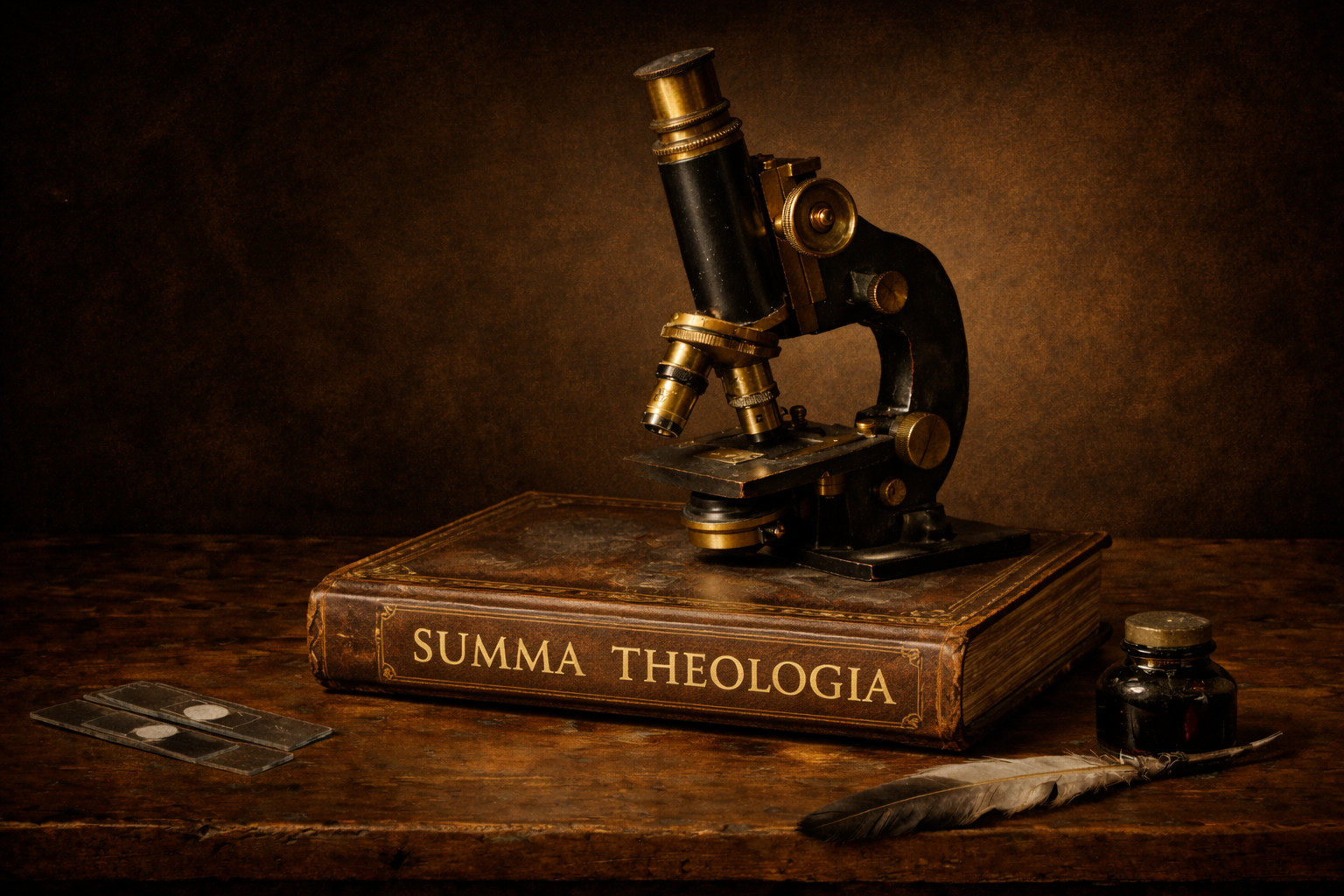

God cannot be found under a microscope, or why concordism is the atheism of believers

Attempt #247 at empirical observation of the Ipsum Esse Subsistens. Result: still nothing. The peer reviewer suggests trying a different instrument. Thomas Aquinas suggests trying a different plane of reality.

"Come on, the Big Bang obviously proves Creation, doesn't it?"

I get asked this question one time too many. And as usual, the short answer is no, the long answer is obviously not, and the full answer requires sitting down, taking a deep breath, and accepting a bit of intellectual suffering. Because we are going to have to resist two symmetrical temptations, both comfortable, both false, and both terribly popular: the one that says science destroys God, and the one that says science proves Him. The former is the armchair atheist's drug of choice; the latter, the lazy believer's sleeping pill.

Let us set the stage.

God Is Not an Experimental Hypothesis

I am a computer scientist by training and by trade. I hold a doctorate in computer science, and I heavily research in artificial cognition (what we call, for lack of a better term, "AI"1), with a neuroscience component that left me with a cross-disciplinary familiarity with the field. I have spent years building models, torturing data, and writing code that refuses to compile at three in the morning. I know the scientific method from the inside, not from some TV philosopher's couch. And it is precisely for this reason that I allow myself to say, with a certain confidence: God is not to be found at the end of an experiment.

Why? Because the experimental method, by construction, deals only with what is measurable, reproducible, and falsifiable. It operates in the domain of secondary causes, natural regularities, observable phenomena. And God (the God of classical metaphysics, not the bearded fellow sitting on a cloud) is not one phenomenon among others. He is, if we follow Saint Thomas, the Ipsum Esse Subsistens, Being Itself subsisting through Itself2. In other words: He is not an object in the world; He is the reason there is a world rather than nothing.

Looking for God under a microscope is like looking for the author of a novel by chemically analysing the ink. You can describe the composition of the ink perfectly, the texture of the paper, the arrangement of the characters... and you will learn strictly nothing about Dostoevsky. Not because Dostoevsky does not exist, but because your method was not made for that. It is perfect for what it does. It is powerless for what it does not.

And that is normal. It is even healthy. A hammer is an admirable tool; that does not make it a screwdriver.

"But the Big Bang, surely..."

Yes, let us talk about it. Seriously, for once.

That Georges Lemaître, Catholic canon and physicist of genius, proposed the hypothesis of the "primeval atom", which became the Big Bang, is a remarkable historical fact. That this theory implies a temporal beginning of the observable universe, well, that seems, at first glance, wonderfully consonant with Genesis. "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth." Well, well.

And that is where the trap snaps shut.

For centuries (yes, centuries) the dominant cosmology did nothing of the sort. Aristotle taught the eternity of the world. The Greeks, in their vast majority, did not conceive of an absolute beginning. And Thomas Aquinas himself, the Angelic Doctor, maintained (listen carefully, this may surprise you) that natural reason cannot demonstrate that the world had a beginning in time3. That it did have a beginning, Thomas believed by faith, on the basis of Revelation. But he refused to claim it was demonstrable by philosophy alone. And if the world had been eternal? Well, said Thomas, God would be just as much its cause. For Creation is not a temporal event; it is an ontological relation of radical dependence.

Do you grasp the lesson? For centuries, the "science" (or rather, natural philosophy) of the time seemed to contradict the biblical account of the beginning. And the Catholic faith did not tremble. It did not need the Big Bang to stand upright. It will not collapse if the Big Bang is one day replaced by something else.

And that is precisely the problem with concordism: it makes faith dependent on the latest fashionable model. Today, the Big Bang "fits" with Genesis, and the concordist rejoices. Tomorrow, if loop quantum gravity or a cyclic cosmological model eliminates the initial singularity4, what does the concordist do? Panic? Lose his faith? Or twist the new theory until it "fits" again?

How wretched.

A Catalogue of Failed Concordisms (and Needless Panics)

Let us take a little tour, shall we, of the domains where the concordist temptation (or its twin, the anti-scientific panic) has done damage. Fair warning: it is not pretty.

Abiogenesis. How did life appear from inert matter? The question is open. Spectacularly open. There are fascinating hypotheses (RNA world, autopoietic systems, proto-metabolisms) but none constitutes, to date, a complete and confirmed explanation. The Sunday concordist exclaims: "You see! Science cannot explain the origin of life! Therefore God!" No. A thousand times no. Just because science has not yet found the answer does not mean God fills the gap. The "God of the gaps" is an idol, not the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Every gap filled by science would then push this poor god a bit further back, until he becomes superfluous. What a miserable god that would be, surviving only in the margins of our ignorance5.

The Catholic position is infinitely stronger: even if science were to explain the origin of life entirely through natural processes, it would take away strictly nothing from divine Creation. For natural causes are secondary causes, which operate within the created order. God is the primary cause: He gives being to the entire system, including the natural laws that make abiogenesis possible. As Thomas would say, the primary cause and the secondary cause are not in competition, any more than the writer and the pen fight over the authorship of the text.

Darwinism. Ah, Darwin. The great fright. The monster under the creationist's bed. You will forgive me for being brief, since the subject would deserve a post of its own: evolution by natural selection is a powerful explanatory framework, widely confirmed, and one that poses no metaphysical problem whatsoever for the serious Thomist. That species transform through natural processes says strictly nothing about the question of why there are species, matter, natural laws, and a universe. Evolution explains the how of the living; it does not touch the why. Confusing the two is the pet sin of both the scientistic and the concordist: the former thinks the "how" suffices; the latter fears the "how" might destroy the "why".

Neither is right. And the believer who rejects evolution out of fear for his faith displays, let us be charitable, a rather fragile faith6.

Monogenism. Here is a more delicate subject, and I treat it with the caution it deserves. Catholic theology teaches monogenism: humanity descends from a first couple (Adam and Eve), and original sin is transmitted by generation. Now, population genetics tends to indicate that humanity does not descend from a single couple, but from a founding population of several thousand individuals. Contradiction?

Perhaps. Perhaps not. It is not for me, a modest blogger, to settle a debate that far more competent theologians and geneticists are exploring with care. I simply note that the question is theologically complex (what do we mean by "Adam"? A historical individual? A representative? Is the notion of "first man" biological or metaphysical?) and that science has not yet said its last word on ancestral population bottleneck models. What matters for our purposes is this: whatever science discovers, the reality of original sin as a wounded condition of humanity does not depend on a model from population genetics. Theology may need to refine its formulations, as it has always done in the face of advancing knowledge. It will not need to change its substance.

Neuroscience. A field I know sideways, through my doctorate in computer science, and which I follow with an interest perhaps a bit too keen for a computer scientist. Believe me nonetheless: this is perhaps the field where the temptation of reverse concordism (let us call it "discordism", shall we) is the most violent. For neuroscience advances, and it shows impressive correlations between brain states and mental states. Such a lesion abolishes such a capacity. Such a stimulation provokes such a sensation. Functional MRI "sees" the brain "thinking" (in quotation marks, because it is infinitely more complicated than that, but let us move on).

And along comes the eliminativist: "You see, there is no soul! It is all neural! Consciousness is an epiphenomenon! Free will is an illusion!" Yes, and the images on your screen prove there is no software behind them, do they not? Cartesian dualism is dead, certainly, and good riddance; but Aristotelian-Thomistic hylomorphism, i.e. the thesis that the soul is the form of the body and not a separate substance floating in the pineal gland, is doing marvellously well in the face of neuroscientific data7. The Thomist expects exactly that brain lesions affect cognitive operations, because the human soul operates through the body. The neuro-mental correlation does not refute the soul; it illustrates the substantial union.

But this is not a scientific argument. It is a philosophical argument. And it is here that the registers must be clearly distinguished.

Near-death experiences. Since we are on the subject of neuroscience and the soul, let us settle this case while we are at it. For the concordist, on the believer's side this time, has his favourite weapon: NDEs (Near-Death Experiences). Tunnel of light, out-of-body experience, encounters with the deceased, a feeling of infinite love... and the faithful cries out, triumphant: "You see! Science proves the afterlife! The soul leaves the body!"

No. Thrice no. And I say this as a Catholic who believes in the immortality of the soul.

First, the facts. NDEs are subjective phenomena reported by patients who have suffered cardiac arrest or a severely altered state of consciousness. These are phenomenological data, that is, testimonies of lived experiences. Now, a lived experience is not a controlled scientific observation. The brain in a state of hypoxia, flooded with endogenous DMT or subject to massive cortical disinhibition, is perfectly capable of producing hallucinations of stupefying intensity and coherence8. That these experiences are real for the person who lives them, I do not doubt for a second. That they constitute empirical proof of the soul's survival after death is a logical leap that rigour forbids.

Then, the theology. The Catholic does not need NDEs to believe in the immortal soul. The immortality of the soul is a philosophical truth (Thomas demonstrates it through the immateriality of the intellect, Summa Theologiae, Ia, q. 75, a. 6) and an article of faith. To hang it on accounts from resuscitated patients is exactly the same concordist trap as hanging Creation on the Big Bang: you make an eternal truth dependent on clinical data that the next study could explain otherwise. The day neuroscience produces a complete model of NDEs through purely neurochemical mechanisms (and that day will probably come) the NDE concordist will lose his "proof", while the Thomist will not have moved an iota.

It is the same error, always the same: confusing a suggestive clue with a demonstration, and building one's faith on what cannot bear it.

Loop quantum gravity. And other cosmological models vying for the title of "theory of everything". I mention them for a precise reason: some of these models eliminate the initial singularity of the Big Bang, suggesting a cosmic "bounce" or a succession of cycles. If such a model were to prevail, there would no longer be a "beginning" in the temporal sense. Crisis of faith? Absolutely not. Reread Thomas Aquinas. An eternal world would be just as much created as a temporal one, because "to create" means "to give being", not "to start the stopwatch". The ontological dependence of the universe on its first cause is indifferent to the arrow of time.

I repeat, because this does not sink in easily: Creation is not the Big Bang. Creation is the metaphysical fact that the universe does not hold its being from itself. Full stop.

Concordism: Anatomy of an Error

Right. Now that we have gone through the examples, let us dissect the beast. What is concordism, exactly, and why is it so noxious?

Concordism is the attempt to make the data of science "coincide" with the claims of faith, by reading sacred texts as anticipations of scientific discoveries, or by interpreting scientific discoveries as direct confirmations of dogma. The "days" of Genesis become geological eras. The Big Bang becomes the moment of Creation. The "firmament" becomes the atmosphere. And so on.

Concordism is seductive, because it reassures. It is deadly, because it makes faith vulnerable to every scientific revolution. If you have built your faith on the "concordance" between Genesis and the cosmology of 2025, you have built on sand. The sand of the provisional state of human knowledge. And the next paradigmatic earthquake (for it will come, it always comes) will sweep away your scaffolding.

Worse still: concordism betrays a profound misunderstanding of what the biblical texts are. Genesis is not a treatise on cosmology. It is not an antediluvian laboratory report. It is a theological text, which speaks of the relationship between God and His creature, of the original goodness of being, of the fall and the promise. Reading Genesis as a physics textbook is like reading a Shakespeare sonnet looking for weather reports. You can do it. But you miss everything.

And the Church has known this for a long time. Saint Augustine, in the fifth century, was already warning against a "scientific" reading of Scripture, noting that nothing discredits Christians more than hearing them assert absurdities in the name of the Bible9. Thomas Aquinas distinguished the four senses of Scripture. Cardinal Bellarmine, facing Galileo, explicitly conceded that the Scriptures would need to be reinterpreted if heliocentrism were demonstrated. The Catholic tradition is, on this point, remarkably consistent: Scripture and reason come from the same God, and therefore cannot contradict each other. If they seem to contradict each other, it is because we have misread one, or misunderstood the other, or both.

The Apologists: Same Mould, Two Waffles

And this is where I must, alas, hand out slaps on both sides of the table. For concordism is not a virus that infects only believers. It has its exact counterpart among atheists, and both species of apologists commit exactly the same error, only in reverse. Same waffle irons, same batter, same results. Only the topping changes.

On one side, the bargain-bin Catholic apologist. You know him. He has read three articles on the Big Bang, a Wikipedia summary on the fine-tuning of cosmological constants, and a Twitter thread on NDEs. And off he goes, triumphant: "SCIENCE proves God! The Big Bang is Genesis! DNA is too complex for chance! Near-death experiences demonstrate the soul!" He thinks he is defending the faith. In reality, he is betraying it. He makes it dependent on a transitory state of research, he confuses suggestive clues with demonstrations, and he turns the God of Exodus into the provisional conclusion of a cosmology paper. The day the model changes, his "proof" collapses, and with it the faith of all those he convinced for the wrong reasons. Bravo. Fine apostolic work.

On the other side, the armchair atheist apologist. This one has read Dawkins (well, the bolded passages), a summary of Dennett, and a few popularisations on neuroscience. And off he goes, equally triumphant: "SCIENCE refutes God! Evolution eliminates the need for a Creator! The brain produces consciousness, therefore no soul! The multiverse makes fine-tuning trivial!" He thinks he is defending reason. In reality, he is caricaturing it. He confuses the scientific method (which is methodologically agnostic by construction) with metaphysical materialism (which is a philosophical position, not an experimental result). He does not realise this, because nobody has ever explained to him the difference between a secondary cause and a primary cause, nor why "science has no need of the God hypothesis" is not the same sentence as "God does not exist"10.

And the most delicious part is that they need each other. The Catholic apologist waves science around like a trophy; the atheist apologist brandishes it like a cudgel. And both presuppose the same thing: that science is the tribunal before which the question of God must be settled. This is false. It is identically false in both cases. The question of God is metaphysical. Science does not settle it, not one way, not the other. The microscope does not see God; it does not see His absence either. It sees cells. That is already very good. Let it do its job.

What exasperates me (and I weigh the word) is that these two camps turn a debate that should be conducted in philosophical rigour into a media ping-pong match where people hurl "studies show that..." at each other's faces, without ever asking what these studies actually show, in what framework they operate, and what questions they are structurally incapable of asking. The result? A public that believes either that science has buried God, or that science has dug Him up. When it has done neither. It has done science. That is sufficient. That is admirable. And it is something else entirely.

Anti-Concordism: The Symmetrical Error

But it would be dishonest to beat only one side. For there exists a symmetrical error, which I will call, for lack of a better term, radical anti-concordism, or epistemic separatism. It is the idea that science and faith are two magisteria so separate that they have strictly nothing to say to each other. Stephen Jay Gould called it NOMA (Non-Overlapping Magisteria): science handles the "how", religion the "why", and the two never cross paths.

It is more presentable than concordism. It is just as false.

Why? Because reality is one. There is not one world for science and another for faith. There is one world, created by one God, and knowable (partially) by one human reason operating in different but not watertight registers. Faith makes claims about reality, not just about "values" or "feelings". When the Creed says "Creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible", it makes an ontological claim, not a poetic one. And when science discovers the structure of reality, it discovers something of Creation.

The magisteria are not watertight, but hierarchised and articulated. Metaphysics grounds what physics presupposes. Physics informs what metaphysics must integrate. And theology crowns the whole, not by dictating results to science, but by asking the questions that science, by construction, cannot ask: why is there something rather than nothing? What is the ultimate foundation of the intelligibility of reality? Does the universe have an end (in the sense of finality, not of terminus)?

The NOMA position is comfortable because it avoids conflict. But it also avoids truth. And avoiding truth for comfort is a sin against the intellect that I refuse to commit11.

The Catholic Position: Demanding, Complex, and Free

So, what is the true position? The one that cheats neither one way nor the other?

I would summarise it thus, as the Sunday Thomist that I am:

First: faith and reason cannot contradict each other, for they proceed from the same God. This is the central affirmation of Fides et Ratio, of Dei Filius (Vatican I), and of the entire Thomistic tradition. If a scientific truth seems to contradict an article of faith, it is because our understanding of one or the other (or both) is insufficient. The Catholic has no reason to fear science. Ever. Under any pretext.

Second: no scientific model can refute the existence of God, in principle. Not because God is "above" science in the sense of an evasion, but because God is not the kind of reality that the experimental method is designed to reach. The question of God's existence is metaphysical, not physical. It belongs to philosophical reason, not to instrumentation. And even Thomas Aquinas's Five Ways are not "experiments": they are metaphysical reasonings that start from common experience (there is motion, there is causality, there is contingency) to ascend to a necessary first cause.

Third, and this is the corollary: no article of faith can legitimately oppose a duly established scientific discovery. The Church has no business telling physicists how gravity works, or biologists how evolution works. If science demonstrates something, the believer must accept it, even if it means refining his reading of Scripture and his theological formulations. For truth does not contradict itself.

Fourth: one must not dogmatise science. A scientific model is, by nature, provisional, revisable, falsifiable. This is its strength, not its weakness. But it means it would be absurd to hang one's faith on the latest model. The Big Bang is our best cosmological model. It may be replaced. So what? Creation is a metaphysical truth, not a cosmological theory. The rational soul is a philosophical truth, not a neuroimaging result. The existence of God is a metaphysical conclusion, not an adjustable parameter of particle physics.

The Catholic position, in sum, is one of intellectual freedom. Freedom to follow science wherever it leads, without fear. Freedom to ask the questions science does not ask, without shame. Freedom to recognise the limits of each discipline, without confusing them. Freedom to seek the total truth, knowing it has a face, and that this face is not that of a data graph.

Conclusion: Truth Is Not Afraid of Itself

I will close with a personal confession. As an artificial intelligence researcher, as a computer scientist who has crossed paths with neuroscience closely enough to bear a few scars from it, as a Catholic, I live daily in this tension between registers. I have read the papers on the neural correlates of consciousness. I have implemented connectionist models that "learn" (the quotation marks are important). I have watched brilliant colleagues conclude, on the basis of their data, that the soul does not exist, that free will is an illusion, that religion is an evolutionary artefact.

And every time, the same thought comes back to me: you are right in your domain, and wrong when you step outside it. Your data are solid. Your metaphysical conclusions are logical leaps. You are confusing the plane of description with that of ultimate explanation. You are like the physicist who, having perfectly described the trajectory of the billiard ball, concludes that there is no player.

There is a player.

And it is precisely for this reason that I do science. Not despite my faith, but because of it. If God is the Creator, then creation is intelligible, ordered, worthy of being studied with the greatest care. Matter is not a veil to be despised; it is the first word of a discourse whose Author is infinite. Every natural law discovered, every mechanism elucidated, every model refined is not a retreat of God, it is one more step in the contemplation of His work. The Thomist does not do science in spite of theology; he does it by virtue of a metaphysics that guarantees the real is knowable, because it proceeds from an Intellect. The more one believes correctly (that is, by distinguishing the planes, respecting the methods, refusing shortcuts) the more science surges forward, free in its movements, unburdened by the fear that the next discovery will bring the sky crashing down. Faith properly understood is not the brake on reason: it is the turbocharger12.

And the contemplation of Truth, whether scientific, philosophical, or theological, is not an exercise in concordance, but a pilgrimage. A pilgrimage where each discipline illuminates one face of the real, where none has a monopoly on the light, and where the serious Catholic agrees to walk without shortcuts.

For God, if He is God, has no need of our argumentative crutches. He does not need the Big Bang to "prove" Genesis. He does not need neuroscience to "fail" for the soul to survive. He does not need evolution to be false to be the Creator.

He is He Who Is13. And Being is not afraid of science.

It is rather science that, if it digs deep enough, should feel the vertigo.

The quotation marks are the bare minimum. The expression "artificial intelligence" is an abuse of language that would deserve a post of its own. Suffice it to say that what we call "AI" has neither intelligence nor artificiality in the proper sense. But that is another subject, and I can already feel my irritation rising.

Summa Theologiae, Ia, q. 3, a. 4. If you have never read this question, do so. It is vertiginous.

Summa Theologiae, Ia, q. 46, a. 2: "That the world did not always exist, we hold by faith alone; it cannot be proved demonstratively." Thomas displays here an intellectual honesty that should make many a hasty apologist blush.

Certain loop quantum gravity models, notably those developed by Martin Bojowald and his colleagues, propose a "quantum bounce" that would replace the initial singularity. Other models, such as Roger Penrose's conformal cyclic cosmology, envisage an infinite succession of aeons. Fascinating, but metaphysically indifferent.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was right on this point, even though I do not share all of his theology: a God who serves only to fill the gaps in our knowledge is a God that knowledge will eventually eliminate. The God of classical metaphysics does not have this problem, because He is not in the gaps: He is the foundation of the totality.

Pius XII, in Humani Generis (1950), was already conceding that the evolution of the human body from pre-existing living matter could be studied and discussed freely, on the condition that the immediate creation of the soul by God be maintained. This is not a recent concession wrung out under academic pressure; it has been the Church's position for over seventy years. Some Catholics still have not read it. So be it.

For the curious, Edward Feser has admirably shown how Thomistic hylomorphism articulates with contemporary neuroscientific data in Philosophy of Mind. I also recommend the work of David Oderberg on the matter. It is dense, but it is serious.

The work of Jimo Borjigin (2023) on post-cardiac-arrest brain activity shows coherent gamma signatures in the dying brain, compatible with intensified states of consciousness. It is fascinating, and it proves or disproves nothing about the soul. It is neurophysiology. Excellent neurophysiology. But neurophysiology.

De Genesi ad litteram, I, 19, 39: Augustine notes that when a Christian speaks on scientific subjects with an assurance grounded in Scripture, but while being factually wrong, it gravely damages the credibility of the faith. Fifteen centuries later, the advice is still current.

Laplace, to whom the famous "I had no need of that hypothesis" about God is attributed, was not doing atheism. He was simply saying that his mechanical model of the solar system worked without direct divine intervention. That is physics, not metaphysics. That the solar system works without God pushing each planet by hand, Thomas Aquinas would have approved without batting an eyelid: it is precisely what secondary causality means. But try explaining that to someone whose entire philosophical education fits in a Reddit meme.

And if you find me arrogant, I remind you that humility is not false modesty. Humility is the truth about oneself. And the truth about myself is that I am a stubborn sinner who tries to think straight. Which is already quite a lot.

It is no accident that the scientific revolution was born in Christian soil. The idea that nature obeys stable and rational laws, discoverable by the human mind, presupposes a metaphysics that neither pantheism, nor occasionalism, nor pure materialism provide as naturally. As Stanley Jaki has shown (Benedictine priest and doctor of physics), modern science needed, in order to be born, the conviction that the world is contingent (therefore not necessary, therefore to be studied empirically) and rational (therefore not chaotic, therefore describable by laws). Guess where that conviction comes from.

Exodus 3:14. אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה. "I Am Who I Am." All of metaphysics fits in those four words.