Why saying one believes 'without proof' is an absurdity, or there is always proof

It's been a while since I've written. For lack of clarity, vision, time and motivation. And because I need time to lay out a reflection, stretch it in all directions, properly appropriate it and be able to understand it. And there are so many interesting subjects that I really have to deal with... But anyway.

I was recently invited to a rather important event, and, during the discussion, someone pointed out to me (with interest):

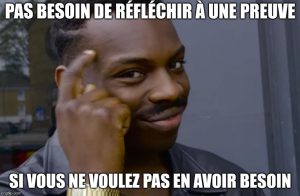

God? I don't believe in it. No proof: you should know that one shouldn't believe without proof...!

This was followed by a brief discussion that ended too soon with a magnificent "ah, but I don't want to discuss religion".

Let's leave aside the thorny question of whether it's possible to have proof of God's existence (I think yes), whether it's possible to understand it (I also think yes), whether it's possible to find proof or reasoning showing it's better to be Catholic (I still think yes, otherwise I wouldn't be writing these lines). Let's also leave aside the classic genetic fallacy of "you say that because you were raised that way", which assumes a hypothetical impossible alternative (for all I know, I could have been deaf, dumb and blind, and therefore with a very different understanding of language) that only amuses a skeptic fond of egocentric mental divergences.

I have a strong aversion to a form of skeptics. A skeptic should remain open and temper the arguments for and against something. However, quite often, you find skeptics repeating "no proof: no reason to believe". In itself, certainly, there's a fundamental difference between affirming and not denying. But, as Raymond Aron points out in his response to Christian Chabanis in "Does God exist? No, answer P. Anquetil, R. Aron, Ch. Boulle, Denise Calippe, Juliette and A. Darle, P. Debray-Ritzen, J. Duclos, G. Elgozy, R. Garaudy, A. Grosser, D. Guérin, E. Ionesco, Fr. Jacob, A. Kastler, Cl. Lévi-Strauss, Isabelle Meslin, Edg. Morin, H. Petit, J. Rostand and J. Vilar": "non-affirmation differs fundamentally from a negation if the mind truly holds itself in a position of equilibrium between affirmation and negation; if it's an oscillating doubt". However, I reproach many of these skeptics for the rest of the quote: "it's a non-affirmation that accompanies the non-search for reasons to affirm, that doesn't accompany a state of uncertainty. So that I believe it's more honest to say that [the] non-affirmation is a way of denying... personally, even more than a simple non-affirmation."

Is it wrong to be a two-speed skeptic? I don't think so. However, it should be specified. It then avoids useless discussions like "but it's OBVIOUS that God exists/doesn't exist" "no that's not true", especially when the initial presuppositions aren't identical. There are many things about which I have no doubt that I would reasonably qualify as skeptical. Thus, for me: ghosts don't exist, walking under a ladder doesn't bring bad luck, it's stupid to compare the idea of God to that of the invisible pink unicorn, etc. Curiously, this often invites an interesting discussion about the definition of the concepts one wishes to have... but few people are interested.

Should we, however, reproach those who think differently, that they believe without proof? To better see this, let's focus instead on the notion of proof. Let's be crazy. This is where all discussion about God and religion, about the paranormal, about beliefs and company starts. Who has never heard the famous quote:

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.

This quote can be traced back to Carl Sagan, in his Cosmos, which he borrowed from the great Marcello Truzzi, probably from a quote by Pierre-Simon de Laplace:

The weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness.

We can finally go back to David Hume, who said:

A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.

Without knowing what "extraordinary" means, let's focus on what "proof" means in this context. Notwithstanding my pejorative view of probabilities and Bayesianism - the context pushing the words - I propose this one, in agreement with the previously cited thinkers1:

A thing is evidence for a second thing if the second thing is more probable given the first thing, than the second thing without considering the first.

A first error is, upon reading, to think that there exists no evidence (in this sense) of something I don't share: my position is true, an opposing position is therefore false, therefore, there can be no evidence against my position.

The proposition indicating that your adversary (in the debate sense) has no evidence for what they claim is always false. Indeed, the simple fact that they hold the position they hold is evidence that the proposition they defend is probably more true than a proposition that no one defends.

Let's go further: even if there's an absolutely false position, if it's held to be true by a certain number of people, we can discern some facts that make it more probable than it would be without these facts, even if the position is actually false. For example, if you play the lottery, that's evidence that you're going to win the lottery, since it increases your chances of winning compared to an identical situation in which you wouldn't play. But yet, you won't win every time, even if you have evidence...

Once you've grasped this, you can start to be wary, if you're really passionate about the search for truth, whether the criteria for defining the burden of proof in a debate are as sharp (and clear-cut!) as people claim. And if you're really interested in the debate, you won't balk at a bit of discussion. Unless you prefer your own echo chamber...

The real question isn't whether there's evidence or not: there's always evidence. The question is: what evidence should I consider valid for my position?

Notes

Yes. I don't really like such a definition, but the person who initially addressed the invective and the embryo of discussion has a scientific background, I must, failing to be able to speak of demonstrative proof (which concerns what can be done by reasoning), speak of immediate empirical evidence, in the sense that a scientist understands it.